When developing the questionnaire format, keep in mind that questionnaires typically have three parts: general instructions, personal information, and the body.

Part 1: General InstructionsThe purpose of the general instructions is to help the person completing the questionnaire have a general understanding of the purpose of the research study, provide a general orientation of the topic of the questionnaire, and describe informed consent. As described on the Research Ethics page, participants have the right to informed consent when participating in a research study, so the researcher must explain the purpose of the research, the requirements of participation, and who is sponsoring the research. Therefore, the general instructions need to include the following:

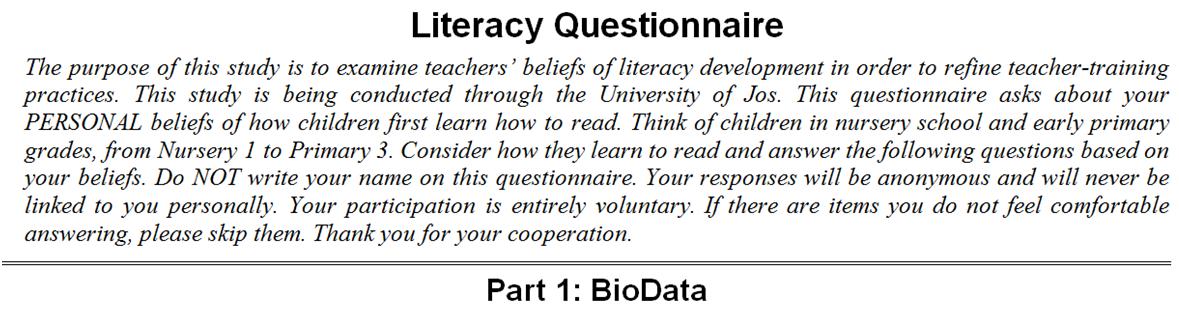

Part of the general instructions also includes the title of the questionnaire. Just as the directions should not lead participants to a desired response, the title also should not bias participants. Again, it is better to keep the questionnaire title as general as possible. A sample of general instructions is:

The specific personal information items were developed in the last step, Writing Questionnaire Items. However, there are a few formatting points that need to be made regarding the personal information.

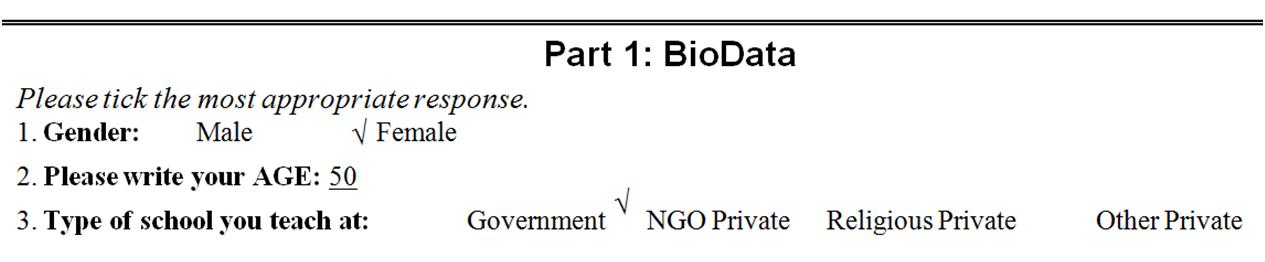

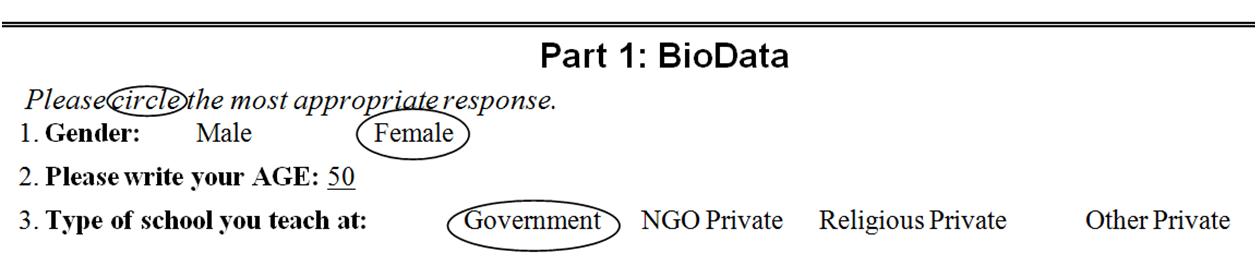

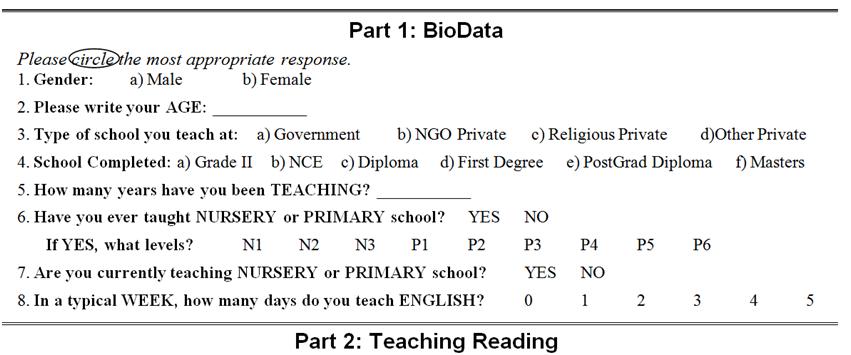

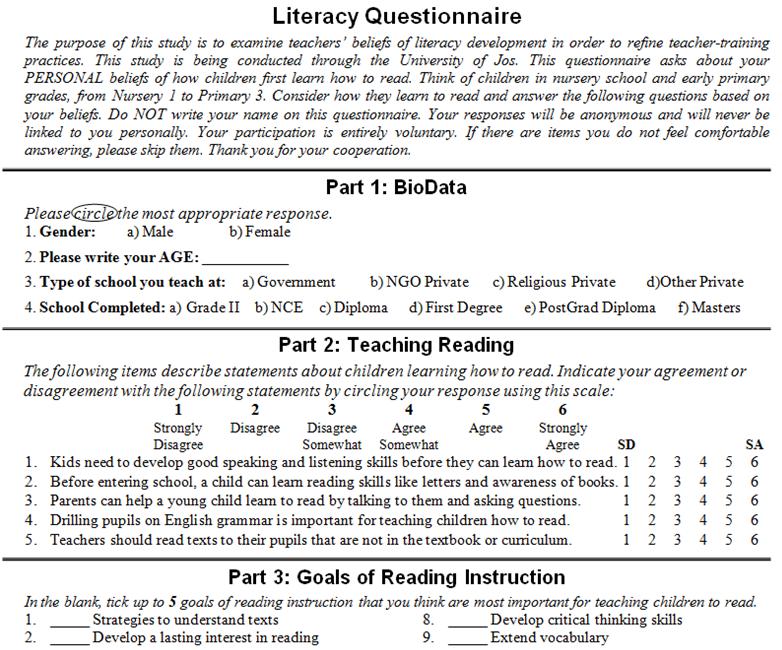

Below is the entire Personal Information section for Korb (2010).

Note how items 1, 3, and 4 have labels so they can be coded. I also chose to have participants write their age so I could know exactly how old they are. Since the questionnaire was designed for teachers, I needed to know what type of school they taught at. Two of the research hypotheses for the study asked about the effect of level of education on teachers' beliefs, and the relationship between years of teaching experience and teachers' beliefs. Items 4 and 5 measure the variables of level of education and teaching experience. The data analysis will statistically determine whether level of education affects teachers' beliefs and whether there is a relationship between teaching experience and teachers' beliefs. Since I was examining teachers' beliefs of early literacy development, I thought that it was also important to determine their experience teaching nursery or primary school and their experiences teaching English.

Specific Instructions

Directions are required every time that participants switch how they respond. For example, the first 20 questions may use Strongly Agree, Agree, etc. The next 10 questions may use Very important, somewhat important, etc. These two sets of items require separate directions. These directions should include the following:

To keep the questionnaire short and clear to participants, do not give them too much information that they do not need. For example, I oftentimes see questionnaires that read "SA=4, A=3, D=2, SD=1, for reverse coded items, SA=1, A=2, D=3, SD=4." Participants do not need to know this information; they only need to know how to respond. This information is only for the researcher when it comes time to code the questionnaire responses, as will be described in Coding Data. Indeed, providing this information will likely confuse the participant. It will also increase the time it takes to complete the questionnaire because the participant will have to read over these confusing directions and think through it, which will cause them to be more fatigued when it comes to information they actually need to know.

Organizing the Questionnaire Items

Once the items have been developed, it is time to organize and format the questionnaire items. When developing the questionnaire items, you probably wrote the items on each variable together: five intrinsic motivation items, six extrinsic motivation items, seven self esteem items, etc. However, on the final questionnaire, it is typically best to mix up the items as long as the items require the same response categories, such as Strongly Agree, Agree, etc. Mixing up the items helps the participants keep alert when reading the questionnaire, and it also masks the fact that many items are similar. Therefore, mix up items that have the same directions and response format. For example, some items may have Strongly Agree responses, and others may have Very Important responses. These two sets of items should obviously be separated. However, if items have the same directions and response formats, then they should be mixed. For example, the order of questionnaire items may be listed as follows. (Only the name of the variable that the item is measuring is listed, not the item itself.)

Formatting the Questionnaire Items

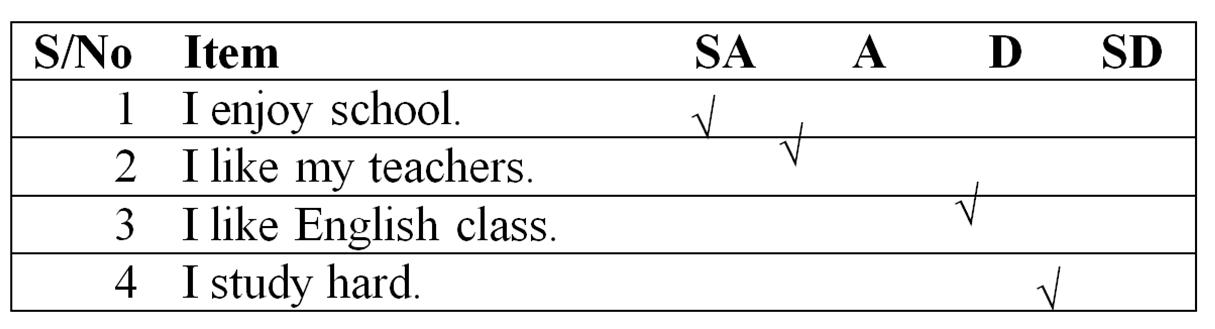

Participants also need to have a space to clearly indicate where they are to respond. I recently evaluated a student who had already collected data from a questionnaire using the following format. What is wrong with it?

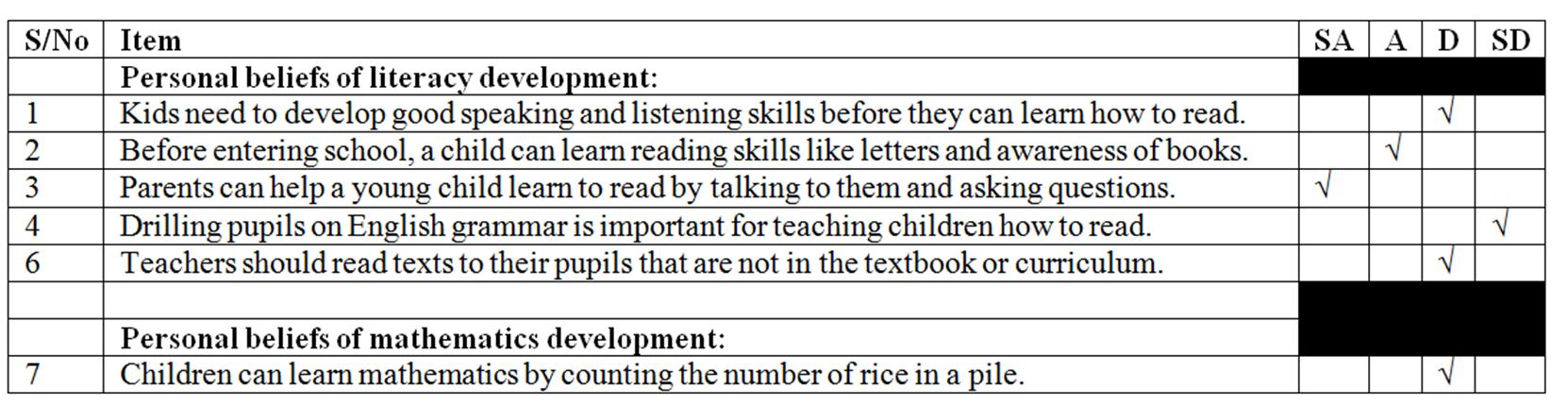

For item 2, did the respondent tick SA or A? What about item 4? Did they intend D or SD? When it comes time for data analysis, it is impossible to know what the participant intended to tick. Guessing will result in serious error, in your data which will invalidate the study's conclusion. The best option is to throw away every questionnaire that is not clear. In this particular case, the student had to discard over 100 questionnaires because it was impossible to determine what the participant had intended to tick.

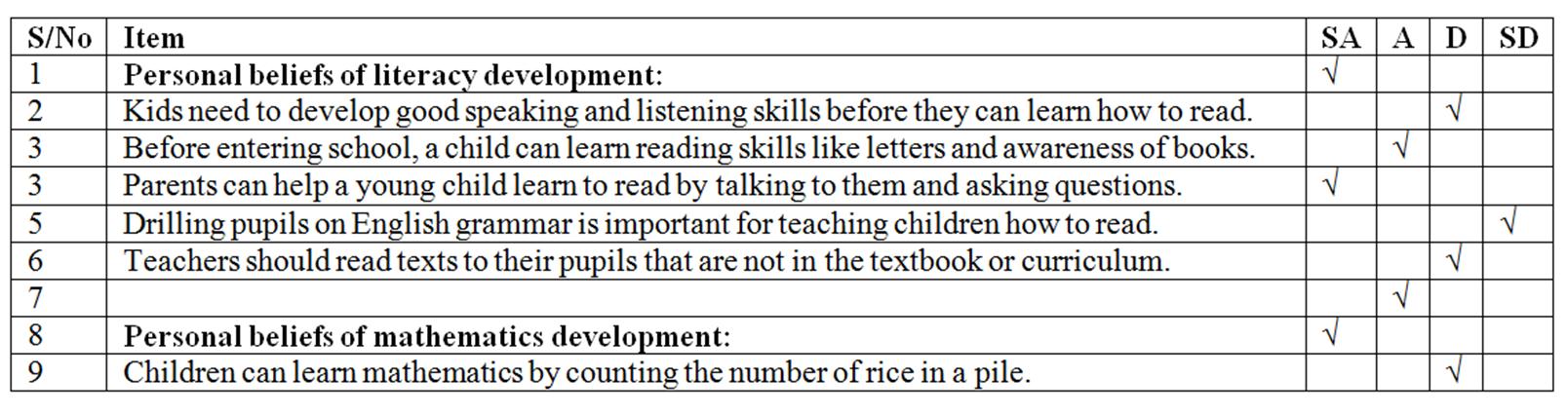

Here is another questionnaire that I recently reviewed. This questionnaire is formatted slightly better, but there is still a serious problem. There are actually three problems with the questionnaire. What is wrong with it?

First, the response categories (SA, A, D, SD) should be described before the items. Second, the serial numbers are wrong - there are two number 3's. . But most importantly, notice item 1. This "item" is really a statement of the types of items that will come. However, the participant ticked a response to this nonsensical statement. Because this statement was numbered, the participant apparently thought that it was an item that needed to be responded to. Can you imagine the confusion of the participant when they saw this questionnaire? That confusion likely confused the participant, and they probably did not respond as they would have if the questionnaire was formatted better and they did not mistake a direction for an item. Likewise, the space in between the first part and the second part (serial number 7) has a box like the participant should respond there. This, too, is quite confusing. There are two ways to avoid this problem. The first is to use a similar tabular format, but somehow indicate that there should not be a response there, by blacking it out as indicated below.

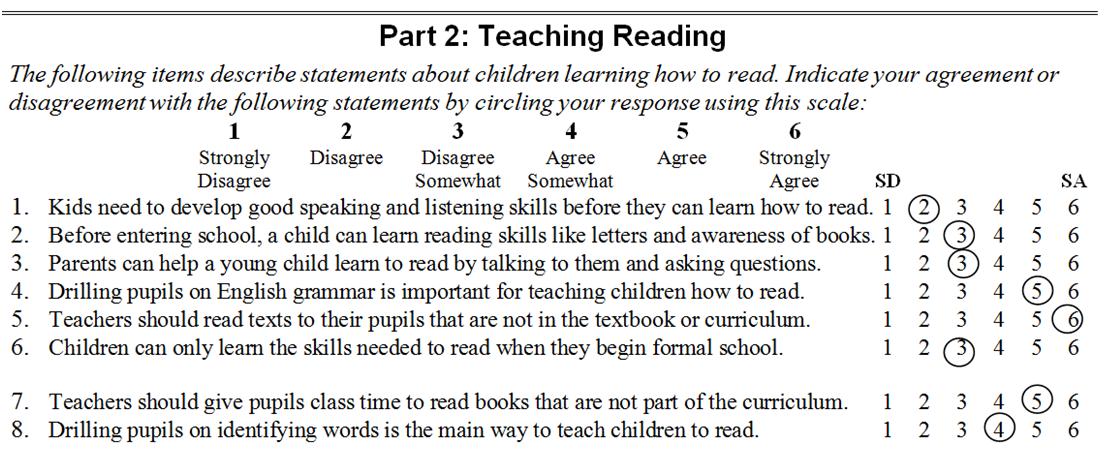

The second strategy to fix this problem is to completely reformat the questionnaire. Another problem with using this tabular format for a questionnaire will present itself when you will be coding your data. If you are going to analyze your data in the computer, you will need to code each participant's response to each item. This is typically done by assigning SA=4, A=3, D=2, SD=1. When the questionnaire is formatted as above, the tick is located in an empty box so it is more difficult to identify whether a tick should be assigned 4 or 3. This can lead to error by the researcher when doing data entry. For these reasons, I prefer to have participants circle the number that corresponds to their response as illustrated below.

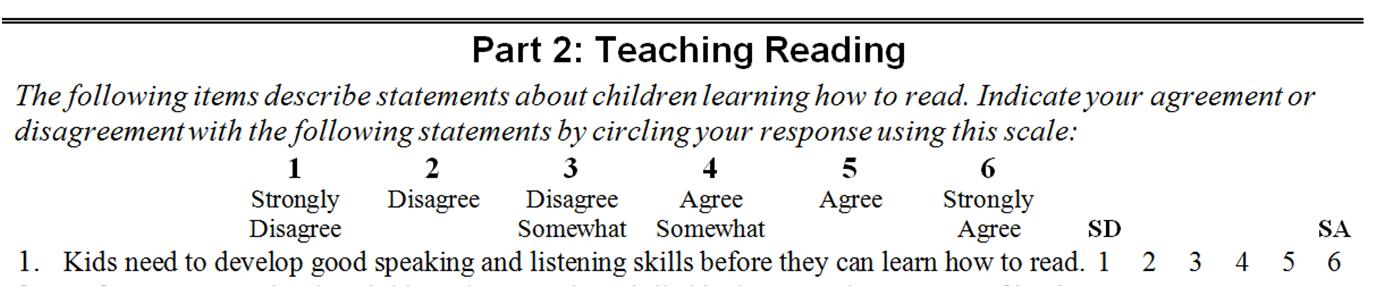

Notice a couple of aspects about this questionnaire. First, the response categories are clearly described at the top. Second, SA and SD are given at the top of the numbers to remind participants of whether Agree is high (6) or low (1). Third, I left a space after item 6 to help make the place to respond more clear. When many items get lumped together, participants can sometimes get confused about which response options correspond to which items and might circle two numbers to one item, and/or skip another item. After every five items or so, I leave a blank space to make the formatting more clear. By circling the numbers, it is clear where participants are to respond to each question. Likewise, data coding is very easy when completed questionnaires are returned.

Conclusion

To summarize, when formatting a questionnaire, keep the following points in mind:

Here is an example of an entire questionnaire. (Note that I cut out a number of items so you can see the entire lay-out.)

When developing questionnaire items, it was mentioned that it is good to read over the questionnaire as if you were a participant. Likewise, when you get a final draft of the questionnaire printed, make one copy of it. Complete the copy of the questionnaire like you are the participant. Are the directions clear? Is it clear how to respond? Is it clear where to respond? Is the formatting appealing? Likewise, read over each question looking for spelling or grammatical mistakes. Make the typist correct any formatting, spelling, or grammatical errors that you find.

Once the questionnaire has been drafted and revised, revised, revised by the researcher and colleagues, then it is time to pilot the questionnaire. The purpose of the pilot study is simply to determine whether the questionnaire is effective for the purposes of the study. Therefore, you are not interested in answering the research questions or testing the hypotheses, but merely interested in whether participants understand the questionnaire, give adequate responses, and the responses can answer the research questions. The pilot study does not need to be large, and a smaller pilot study can actually be more effective because the researcher can then talk to the participants and ask them what they were confused about on the questionnaire. After getting results from the pilot study, make corrections to the questionnaire. If significant changes are necessary, then the researcher needs to conduct a second pilot study and make more changes. The pilot studies are finished when the researcher is finished making substantial changes to the questionnaire.

Return to Educational Research Steps

Copyright 2012, Katrina A. Korb, All Rights Reserved