Researchers have an ethical responsibility for conducting high quality research. High quality research mandates that the instrument be developed professionally. Developing a questionnaire is not an easy task and it takes much time, thought, and effort by the researcher. I recently collaborated with two other senior researchers to develop a 23-item questionnaire. We worked intensively for two months on the questionnaire, conducted three separate pilot studies, and made nine drafts before we finally settled on a final copy of that questionnaire. If you develop your own questionnaire, be sure to allow plenty of time for planning, reviewing literature, and revising the instrument. Allow at least a month for developing a high-quality instrument.

The researcher has the responsibility to create an instrument in such a manner so that will be understandable to whomever will be taking the instrument. Anything that causes a participant to give a wrong answer on the instrument is called error. Researchers must be very careful to make the instrument as clear as possible to avoid error. This means that the researcher must spend considerable time carefully developing the instrument, revising the instrument, pilot testing the instrument, and correcting the instrument.

It is important to make the instrument as clear as possible so that no additional explanations, directions, or comments should be necessary beyond what is present on the questionnaire itself. This means the directions are clear, the items are well written, and the formatting is professional so that participants understand where to respond.

The first step in developing an instrument is to consider the population under study. A questionnaire for children in Primary 5 will be different than a questionnaire for university students, even if it is measuring the same variable, such as intrinsic motivation. To ensure that the instrument is understandable to the population, the instrument must have appropriate directions, clear and understandable language, and concepts that the participant can understand. For example, a researcher might be interested in whether a primary school teacher gives lessons on phonemic awareness. However, "phonemic awareness" is a technical term that a teacher might not understand. Because of this, a questionnaire item cannot read "Do you teach phonemic awareness?" Instead, the item should use language that the teacher will understand, such as "Do you teach lessons about the individual sounds within words?"

It takes time and effort by the participant to complete the instrument. When filling the instrument, participants get tired and rushed and this can also be a source of error, particularly on the last items of the instrument. Therefore, keep the questionnaire as short as possible while still including enough items to adequately measure the variables of interest. The best way to keep the questionnaire short is to only write items that measure the variables from the Research Questions and Research Hypotheses. Any irrelevant questions should be canceled.

Oftentimes, researchers try to measure their participants' perceptions of a phenomenon, which does NOT result in a valid research study. People can report on their own demographic characteristics (also called biodata), attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, feelings, and behavior. However, people can rarely report other people's attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, feelings, and behavior with 100% accuracy because it is impossible for us to really know somebody else's thoughts. For example, a teacher might think she knows how well her students enjoy a lesson, but it is much better to ask the students themselves how they feel about the lesson. Because a teacher does not really know what the students are thinking, asking teachers to report on students is a huge source of error. Therefore, researchers should always ask a person directly about their own thoughts. If a person is asked to report on something they have not directly experienced, such as a teacher reporting on student interest, then the topic should be rephrased to include either the word belief or perception: "Teachers' beliefs of student interest" or "Teachers' perceptions of student interest", not "Student interest." A researcher must find the most direct way to measure a variable to avoid error.

To illustrate the point that the key variables must be directly measured, I conducted a little research study where I administered a questionnaire to 42 students who were working on their Masters degree in education. I asked the masters students about their beliefs of a number of well established psychological findings. For example, high quality research has strongly demonstrated that giving material rewards to students actually decreases their interest in a subject (see the Self Determination Theory website or click here to read a story that illustrates this point). In the questionnaire, the masters students were to respond Yes or No to five questions about whether giving a reward to students would increase or decrease their interest in an activity. For example, one question read: "A child will enjoy an activity more if they receive money for doing it."

Were the masters students accurate in their beliefs? On the question above, the correct answer is NO, children do not enjoy an activity more if they receive money for doing it. (A child may enjoy the money, but their enjoyment in the activity will not improve. Instead, their motivational focus is on the money, not on the activity.) However, only 18% of the masters students correctly answered this question! If most masters students (82%) do not have accurate beliefs about all educational phenomenon, then it is impossible for students, parents, teachers, and other educational stakeholders to accurately report on their beliefs of educational phenomenon!

Asking participants about their beliefs of educational variables has so much error that any conclusions drawn from these types of studies are not valid! Instead of asking people to report their beliefs or to report about somebody else, find a way to directly measure each variable. To do this, each item must reflect the construct definition of the variable that you developed in Developing Instruments. More information on how to directly measure a variable will be described below.

Summary

When developing a questionnaire, follow the following guidelines.

The following guidelines are specific to developing a questionnaire. Most of these suggestions apply to a checklist and an interview, although a few specific comments about developing a checklist will be described below.

Most questionnaires typically start with questions about the participant. Personal information can also be called demographic characteristics or biodata. Consider only those items that are essential to getting a good understanding of your sample and that answer your research questions. In the interest of keeping the questionnaire as short as possible, extra questions that are unrelated to the research questions or hypotheses should typically be canceled.

Do not simply copy the personal information items from another questionnaire. Oftentimes, this information will be completely irrelevant to the purposes of your study. Instead, consider which variables are relevant and capture information important about your study. For example, I just reviewed a questionnaire that was going to be given to a sample of university students. The questionnaire asked participants to tick whether they were a student or staff at the university. Obviously, if the questionnaire is designed for students, this item is unnecessary! I have also seen other questionnaires designed for Junior Secondary Students. In the Age item, they were given the options of ticking 15-20; 21-25, and 26 and above. Some JSS students are under 15, and virtually all others will fall in the 15-20 range. These items do not reflect thoughtful preparation by the researcher.

When developing personal information items, keep the following considerations in mind.

This is the real substance of the questionnaire. Examine the list of variables with their accompanying construct definitions and operational definitions from the beginning of Developing Instruments. Each variable requires a number of items (typically between 4 to 10 but this can vary based on the variable and logistical considerations) that measure the variable directly and are directly related to the construct definition of the variable. For example, imagine a research study measuring classroom attendance. What is the most direct way to measure classroom attendance? Is it items on a questionnaire that ask participants whether they agree that people should attend class regularly? Or is it the record of classroom attendance from the school? As the construct definition of attendance would likely be "number of days that the student attends class," the latter method of measurement is most direct, and therefore most desirable.

As a second example, consider the variable intrinsic motivation, defined as "The motivation for a behavior that is based on the inherent enjoyment in the behavior itself." A researcher might be tempted to write an item that says, "I work hard in school" to measure intrinsic motivation. However, this item does not directly relate to the construct definition presented earlier. The researcher might argue that if a pupil enjoys going to school, then they will then work harder. However, there is a difference between "working hard" and "enjoying" something. A student might work hard in school because his father will beat him if he performs poorly, but that student might thoroughly hate school. This student would respond "Strongly Agree" to the item, but have low intrinsic motivation in reality. If a participant ticks Strongly Agree, that means they are high on the construct definition, and a participant who ticks Strongly Disagree should be low on the construct definition. Therefore, all items must center around the construct definition - enjoyment in the case of intrinsic motivation. A good item for intrinsic motivation might read: "I enjoy going to school."

Keep in mind the analogy of an examination: people who score higher on an exam should have a higher knowledge of the subject, whereas people who score lower on the exam should have less knowledge of the subject. Likewise, people who tick "strongly agree" should be higher on the variable of interest than those who tick "strongly disagree." If it is possible for a participant to be high on the variable, yet tick "disagree," then it is a bad item.

Remember that good questionnaire items must:

When developing questionnaire items, AVOID:

It is also possible to write items that are reverse coded. This simply means that the items are the reverse, or the opposite, of what is truly desired. If questions continually read, "I enjoy going to school," "I like going to school," "Going to school is fun for me," etc., then participants might start to tick SA, SA, SA without thinking about their responses. Therefore, in many cases, it is good to also write items that mean the opposite: "I do NOT like going to school." This keeps participants alert when responding, and it also prevents the problem of acquiescence bias, the tendency to agree with every statement.

As an illustration of developing questionnaire items, consider the variable meaningful reading from the teachers' beliefs of literacy development study. The construct definition of meaningful reading was: "The belief that young children should both read meaningful literature and have meaningful literature read out loud to them (books that are enjoyable, relevant, and are not necessarily part of the curriculum) because it helps improve their literacy skills." The operational definition was: "Meaningful reading will be measured by teachers' agreement to four self-report statements of their beliefs on meaningful reading on a six-point Likert scale." The four items based off of this definition were:

Practice

Below, I present some bad questionnaire items. Read over each item and consider what might be wrong with the item.

Tips for Writing Questionnaire Items

When writing the items on a questionnaire, keep the following tips in mind:

Tips for Writing Questionnaire Options

Oftentimes, educational researchers use Likert Scale fformat for responding, which asks participants to indicate their level of agreement to statements. Typically, the options are various levels of Strongly Agree, Agree, Agree Somewhat, Disagree Somewhat, Disagree, or Strongly Disagree. Some people also use a Neutral category. A Neutral category is good for participants who do not have an opinion about a particular statement. A researcher's personal preference and/or the variable under study determine whether a Neutral or No Opinion category is used. I generally personally prefer not to use a Neutral because I typically prefer that my participants think about the statement and make a choice. I feel that giving a Neutral option allows participants to be lazy and not think about an item.

The Likert Scale is not the only scale that is available for responding, though, and many research studies require that other continuous options are used. For example, I have given the following directions:

A questionnaire can also use a "Pick your top choices" option. For example, read the following item:

Please circle the four (4) biggest reasons why reading is important.

Checklists like this can also be used to calculate the frequency of behaviors. For example, checklists are often used to determine whether somebody has a mental illness. A list of symptoms of depression, such as fatigue, loss of appetite, and feelings of sadness, are listed. Participants tick all symptoms they have experienced within a specific timeframe (perhaps six weeks, six months, etc.). If a person has experienced a certain number of symptoms, then they are classified as being depressed.

Likewise, participants could also tick the number of behaviors they have done in other domains. A researcher interested in cheating might present a list of various types of malpractices (e.g., copying an assignment, bringing in a cheat sheet to an exam, writing answers on their body, etc.) and ask participants to tick which malpractices they have engaged in within a specific period of time (i.e., 1 year, in university, etc.). Instead of ticking, participants could circle either "Yes" or "No." Checklists are also useful for researchers when they are observing participant behavior. I explain a bit more about collecting observations at the end of this page.

Once you have finished developing questionnaire items, you need to spend substantial time revising those items even before giving it to somebody else to review for you. Here are some tips for revising the items:

Oftentimes, educational researchers are interested in actual participant behaviors. A major topic of interest to educational researchers is teaching methods in the classroom. For example, does a teacher use good questioning techniques? Does a teacher appropriately engage all students? What is a teacher's classroom management style? These types of variables are most directly measured by watching a teacher in the classroom and recording observations of the teacher's behavior.

Just a reminder that observation is best used when measuring behavior. Using observation to measure feelings and attitudes can be tricky. For example, a person might be tempted to observe whether a person drinks a Maltina to determine their attitude toward Maltina, the logic being that they have a positive attitude toward Maltina if they drink it and have a negative attitude toward Maltina if they don't drink it. However, there are many reasons why a person might drink Maltina and have a negative attitude toward it: they were thirsty and it was the only beverage available, they wanted to be polite, etc. Likewise, there are many reasons why a person might not drink a Maltina but they may still like it: they were not thirsty, it was too expensive, they were about to go on a long car trip, etc. In general, behaviors are best measured by observation while feelings and attitude are best measured by self report questionnaire or checklist.

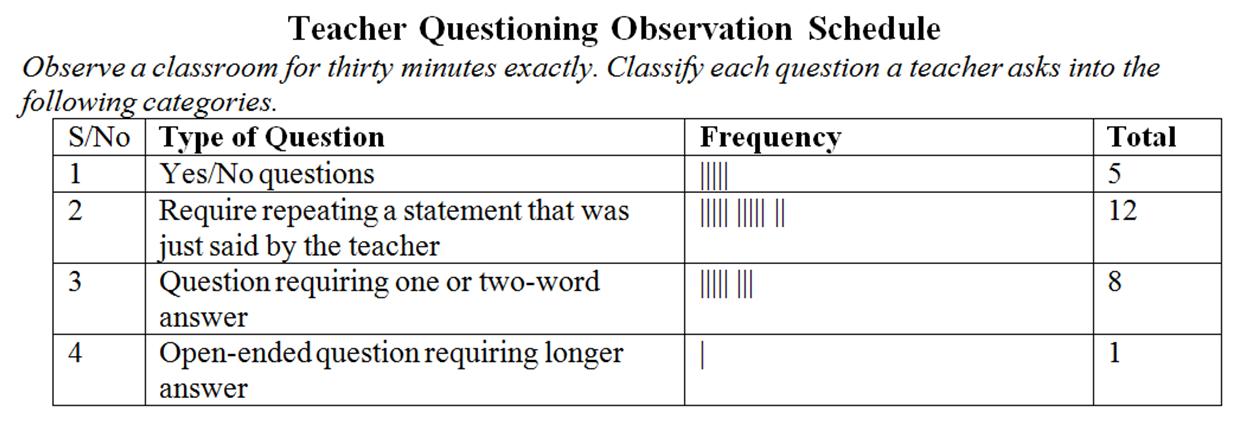

Just as variables measured by questionnaire first need to be operationally defined, so too do variables measured by observation. Once the operational definition is given, make a list of behaviors to be observed. If the variable to be observed is type of questions that teachers ask, then the researcher must consider the types of questions of interest? Perhaps a list of relevant questions may include:

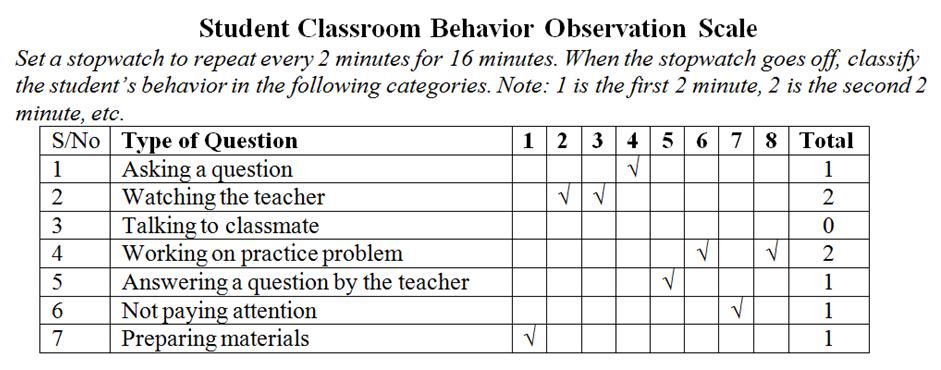

Once the list of behaviors has been developed, then the researcher needs to determine how the behaviors will be observed. Consider the following questions:

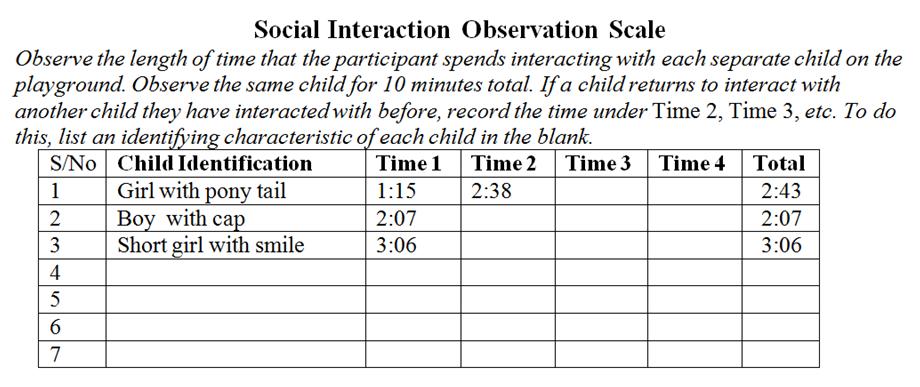

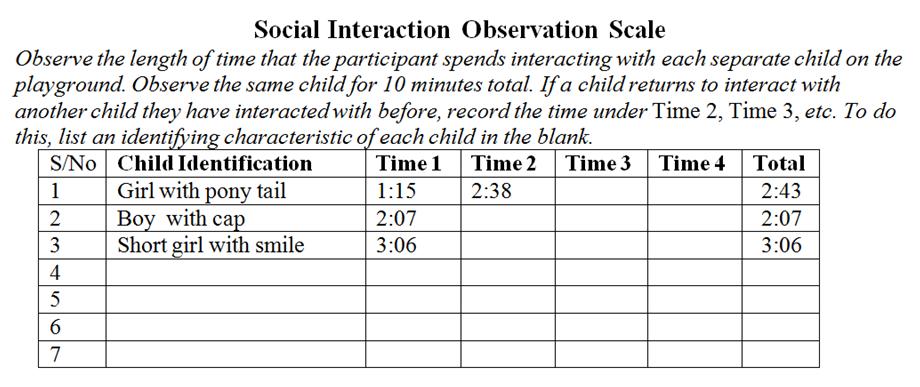

Once these questions have been answered, then the researcher should develop an observation scale, a form where the observer records behaviors. Observation schedules are for the researchers' and research assistant's use, so they do not have to be quite as detailed as questionnaires. Example observation schedules are given below.

Duration Observation Schedule

Frequency Count Observation Schedule

Interval Observation Schedule

Once the observation scale has been developed, it needs to be piloted a few times to ensure that the categories are clear, the categories are sufficient (i.e., there are not any more behaviors that should be added), and the observational guidelines are effective.

When the final observation schedule is finished, then all research assistants who will be observing in the study need to be thoroughly trained on using the schedule. First, the observation schedule should be discussed so the research assistants understand how to use the observation schedule and understand each of the categories. Then, each research assistant should do practice observations. It is best to ask all research assistants to observe the exact same behavior so disagreements on how a specific behavior should be classified can be discussed.

Keep the following additional considerations in mind when developing an instrument.

Return to Educational Research Steps

Copyright 2012, Katrina A. Korb, All Rights Reserved